Kicking off with How to Slice a Model for Maximum Strength, this opening paragraph is designed to captivate and engage the readers, setting the tone for a comprehensive exploration of achieving unparalleled structural integrity in your 3D printed creations. Understanding the intricate interplay between material science, geometric design, and precise slicing software configurations is paramount for unlocking the full potential of your models.

This guide delves into the essential principles and practical techniques required to transform ordinary designs into exceptionally robust objects. We will navigate through the fundamental material properties that dictate strength, explore how geometric features contribute to durability, and dissect the critical slicing settings that directly impact a model’s load-bearing capacity. Furthermore, we will uncover advanced strategies and the vital role of testing and iteration in perfecting your models for maximum resilience.

Understanding Material Properties for Strength

To achieve a model with maximum structural integrity, a deep understanding of the materials used is paramount. This involves delving into the fundamental principles of material science that govern how a substance behaves under stress and strain, ultimately determining its ability to resist deformation and failure. By comprehending these properties, we can make informed decisions during the design and slicing phases to optimize for strength.The inherent characteristics of a material dictate its performance when subjected to external forces.

These characteristics influence how readily a material deforms, how much energy it can absorb before permanent damage occurs, and at what point it will fracture. Identifying these critical attributes allows for a proactive approach to reinforcing vulnerable areas and selecting appropriate materials for specific applications.

Fundamental Material Science Principles for Structural Integrity

The structural integrity of any model is intrinsically linked to the fundamental behavior of its constituent materials when subjected to mechanical loads. Material science provides the framework for understanding these behaviors, focusing on how atoms and molecules arrange themselves and interact, which directly translates into macroscopic properties like strength and stiffness.Key principles include:

- Atomic Bonding: The type and strength of chemical bonds (ionic, covalent, metallic) between atoms determine a material’s inherent resistance to deformation. Stronger bonds generally lead to higher strength.

- Microstructure: The arrangement and size of grains, phases, and defects within a material significantly impact its mechanical properties. For instance, smaller grain sizes often result in higher yield strength due to increased grain boundary area impeding dislocation movement.

- Crystal Structure: The specific arrangement of atoms in a crystalline solid (e.g., face-centered cubic, body-centered cubic, hexagonal close-packed) influences its ductility and strength. Some crystal structures allow for easier slip, leading to greater deformation before fracture.

- Defects: Imperfections in the crystal lattice, such as vacancies, interstitials, and dislocations, play a crucial role. While some defects can weaken a material, controlled introduction of others, like dislocations, is essential for plastic deformation in ductile materials.

Common Material Characteristics Influencing Stress and Strain Resistance

When considering how a model will withstand stress and strain, several common material characteristics are of primary importance. These properties provide quantifiable measures of a material’s mechanical response, guiding our choices in design and manufacturing.The following characteristics are critical for assessing a material’s ability to resist deformation and failure:

- Tensile Strength: The maximum stress a material can withstand while being stretched or pulled before breaking.

- Yield Strength: The stress at which a material begins to deform plastically, meaning it will not return to its original shape once the load is removed. This is often a more practical measure of a material’s usable strength than ultimate tensile strength.

- Compressive Strength: The maximum stress a material can withstand while being pushed or squeezed before failing.

- Modulus of Elasticity (Young’s Modulus): A measure of a material’s stiffness, indicating how much it will deform elastically under a given stress. A higher modulus means a stiffer material.

- Ductility: The ability of a material to deform plastically under tensile stress without fracturing. It is often measured by elongation at break or reduction in area.

- Toughness: The ability of a material to absorb energy and deform plastically before fracturing. It is a combination of strength and ductility.

- Hardness: Resistance to scratching, abrasion, or indentation. While not directly a measure of bulk strength, it is often correlated with yield strength.

Methods for Identifying Critical Stress Points

Understanding where a model is most likely to experience failure is crucial for reinforcing it effectively. Critical stress points are typically located in areas where forces concentrate or where the geometry introduces discontinuities.Various methods can be employed to identify these vulnerable regions:

- Finite Element Analysis (FEA): This is a powerful computational tool that simulates the behavior of a structure under various loads. By dividing the model into smaller elements, FEA can predict stress and strain distributions with high accuracy, highlighting areas of maximum stress concentration.

- Stress Concentration Factors: These are dimensionless numbers that quantify how much stress is increased in the vicinity of a geometric discontinuity, such as holes, notches, or sharp corners. Understanding these factors allows for an analytical prediction of high-stress areas.

- Experimental Stress Analysis: Techniques like photoelasticity, strain gauging, and brittle coating can be used on physical prototypes to measure actual stress distributions under load. These methods provide real-world validation of theoretical predictions.

- Fracture Mechanics Principles: Analyzing crack initiation and propagation can help identify areas prone to fatigue failure or brittle fracture, particularly in components subjected to cyclic loading or sharp notches.

Anisotropic vs. Isotropic Materials and Their Impact on Slicing for Strength

The directional nature of material properties significantly influences how we should approach slicing for maximum strength. Materials can be broadly categorized as either isotropic or anisotropic, each requiring distinct strategies.

Isotropic materials exhibit uniform properties in all directions. This means their strength, stiffness, and other mechanical characteristics are the same regardless of the direction of applied force. For isotropic materials, the orientation of the printed layers typically has a less pronounced impact on overall strength, as the material behaves predictably in all orientations.

In contrast, anisotropic materials possess properties that vary with direction. This anisotropy is often a direct consequence of their internal structure, such as the alignment of polymer chains in plastics or the grain orientation in metals. For additive manufacturing, layer adhesion is a critical factor, and the direction of printing relative to the applied load becomes paramount.

The impact on slicing for strength is profound:

- For Isotropic Materials: While layer orientation is less critical for bulk strength, ensuring good inter-layer adhesion is still important for overall structural integrity, especially against shear forces between layers.

- For Anisotropic Materials: Slicing must be carefully considered to align the material’s strongest properties with the anticipated stress directions. For example, if a material is stronger along the direction of its extrusion or fiber alignment, the slicing orientation should be chosen so that these strong directions are aligned with the primary load-bearing paths in the final model. Poor orientation can lead to significantly weaker parts, as the load may be applied along a direction where the material is inherently weaker.

Geometric Considerations for Enhanced Durability

Beyond material properties, the very shape and form of your 3D model play a critical role in its structural integrity. Thoughtful geometric design can significantly enhance a model’s resistance to breakage, making it more robust and reliable for its intended application. This section delves into the key geometric features that contribute to increased durability.

Inherent Strength Through Geometric Features

Certain geometric configurations naturally lend themselves to greater strength. Understanding these principles allows for proactive design choices that minimize stress concentrations and distribute loads effectively.

- Ribs and Gussets: These are structural elements that add rigidity to flat surfaces or connect different parts of a model. Ribs are typically thin, elongated supports that run along a surface, while gussets are triangular or curved supports used at corners or junctions. They increase the moment of inertia of a component without adding excessive material, thus improving stiffness and strength.

- Fillets and Chamfers: These are rounded or beveled edges, respectively. They are crucial for reducing stress concentrations that occur at sharp corners. Stress tends to build up at points of abrupt geometric change, making them prone to cracking. Introducing fillets and chamfers smooths these transitions, allowing stress to distribute more evenly.

- Hollow Structures with Internal Supports: While solid models can be strong, they can also be material-intensive. Strategically hollowing out a model and incorporating internal support structures, such as lattices or honeycombs, can achieve comparable strength with reduced weight and material usage. The design of these internal supports is critical to their effectiveness.

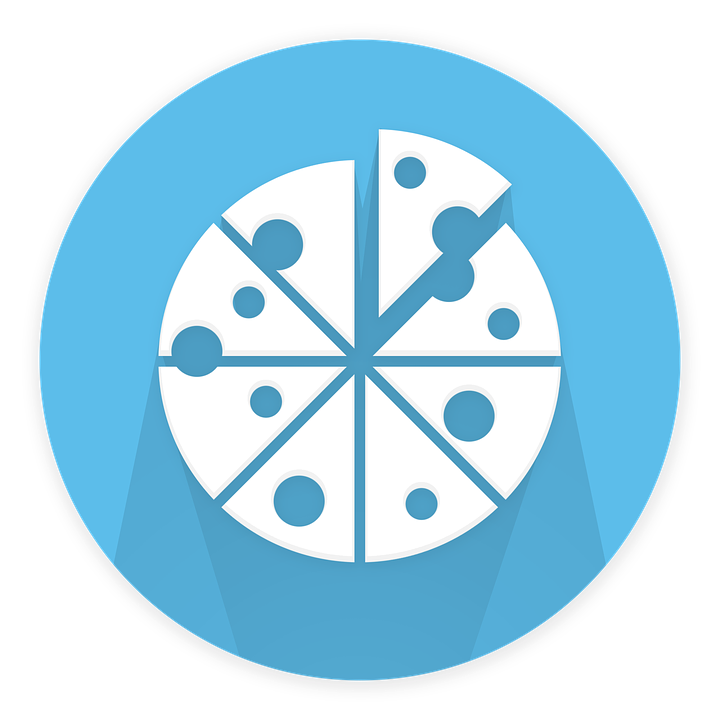

The Impact of Wall Thickness and Infill Density

Wall thickness and infill density are two of the most fundamental parameters controlled during the slicing process, and they have a direct and substantial impact on a model’s strength.The wall thickness, also known as shell thickness or perimeter count, refers to the thickness of the outer layers of the 3D print. Thicker walls provide more material to resist external forces and prevent delamination.

For instance, a part designed to withstand significant bending forces will benefit greatly from thicker walls, as they increase the cross-sectional area resisting the bending moment. Infill density determines the amount of material printed within the model’s outer shell. A higher infill density means more internal material, leading to a stronger and heavier part. However, the pattern of the infill also matters.

Patterns like gyroid or cubic are known for their good strength-to-weight ratio and ability to distribute stress in multiple directions, whereas simpler patterns like grid might be weaker in certain orientations. For maximum strength, a higher infill density, often approaching 100% for critical components, is generally recommended. However, it’s important to balance strength requirements with material cost and print time.

Reinforcing Vulnerable Areas Through Geometric Modification

Identifying and reinforcing areas prone to failure is a key aspect of designing for durability. Vulnerable areas often include:

- Corners and Edges: As mentioned, sharp corners are stress concentrators. Adding fillets or chamfers to these areas is a primary method of reinforcement.

- Thin Sections: Areas where the model’s geometry is inherently thin are susceptible to bending or snapping. Increasing the wall thickness in these specific regions or adding supporting ribs can dramatically improve their strength.

- Attachment Points: If the model needs to be attached to another component or has holes for fasteners, these areas require special attention. Widening the base of a hole, adding a reinforcing boss around it, or increasing the wall thickness in the immediate vicinity can prevent tearing or cracking.

- Areas Under High Load: Analyze where the model will experience the most stress during its use. These areas can be reinforced by increasing the local wall thickness, adding internal bracing, or changing the geometry to distribute the load over a larger surface area. For example, a cantilevered arm designed to hold weight might be strengthened by tapering its base and adding a fillet where it connects to the main body.

Sharp Corners Versus Rounded Edges

The distinction between sharp corners and rounded edges is paramount when considering the mechanical performance of 3D printed objects.

Sharp corners are notorious for concentrating stress. When a force is applied to an object with sharp corners, the stress lines tend to bunch up at these points, much like water flowing through a narrow channel. This localized high stress can easily exceed the material’s yield strength, leading to crack initiation and eventual failure.

In contrast, rounded edges, achieved through fillets, offer a smoother path for stress distribution.

| Feature | Strength Implication | Durability Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Sharp Corners | High stress concentration. | Prone to cracking and premature failure under load. |

| Rounded Edges (Fillets) | Even stress distribution. | Significantly increases resistance to fracture and fatigue. |

| Beveled Edges (Chamfers) | Reduces stress concentration compared to sharp corners, but less effectively than fillets. | Improves durability by smoothing transitions, especially useful for assembly or handling. |

For 3D printed parts, especially those subjected to dynamic loads or cyclic stress, the use of rounded edges is a fundamental design principle for maximizing lifespan and preventing catastrophic failure. While sharp corners might be aesthetically desired in some contexts, they should be avoided in areas critical for structural integrity.

Slicing Software Settings for Structural Integrity

To achieve maximum strength in a 3D printed model, the settings within your slicing software play a pivotal role. These parameters dictate how the material is deposited layer by layer, directly influencing the internal structure and external integrity of the final print. Optimizing these settings requires a nuanced understanding of how each variable contributes to the overall load-bearing capacity of the object.

This section will guide you through the crucial slicing parameters that directly affect a model’s strength, providing a systematic approach to achieving robust prints.Selecting the appropriate slicing software settings is paramount for ensuring that your 3D printed parts can withstand the intended mechanical stresses. Without careful consideration, even the strongest materials can result in weak prints due to suboptimal layer adhesion, insufficient material density, or poor structural design within the print itself.

By fine-tuning these parameters, you can significantly enhance the durability and performance of your models, making them suitable for demanding applications.

Layer Height and Print Speed Optimization

The interplay between layer height and print speed is fundamental to achieving strong prints. A smaller layer height generally leads to better layer adhesion, as it allows for more complete melting and fusion of successive layers. However, printing with very small layer heights can significantly increase print time. Print speed, conversely, affects the cooling rate of the extruded filament. Printing too fast can result in incomplete layer bonding, while printing too slow might lead to excessive heat buildup and material deformation.To optimize these settings for strength, a step-by-step approach is recommended:

- Start with a Baseline: Identify the recommended layer height and print speed for your specific filament material and printer. For instance, PLA often prints well at 0.15mm to 0.2mm layer height and speeds between 40-60 mm/s. ABS might benefit from slightly larger layer heights (0.2mm-0.3mm) and potentially slower speeds to ensure good adhesion.

- Reduce Layer Height: Gradually decrease the layer height in small increments (e.g., from 0.2mm to 0.16mm, then to 0.12mm). For each reduction, perform a small test print of a simple tensile bar or a block that will be subjected to stress.

- Adjust Print Speed Accordingly: As you decrease the layer height, you may need to slightly reduce the print speed to ensure adequate melt pool and adhesion. Conversely, if you are increasing layer height for faster prints, ensure your print speed is not so high that it compromises layer bonding. A common guideline is to maintain a volumetric flow rate (how much plastic is extruded per second) within the capabilities of your hotend.

- Test Layer Adhesion: After printing test pieces with different settings, subject them to bending or tensile stress to evaluate layer adhesion. Look for signs of delamination or easy separation between layers. The settings that resist delamination best while maintaining reasonable print times are generally optimal.

- Consider Outer Wall Speed: While infill speed is important, the speed at which the outer walls are printed is critical for surface integrity and resistance to external forces. Often, reducing the outer wall print speed slightly can significantly improve the final part’s strength and surface finish.

Infill Patterns for Robustness

The infill pattern defines the internal structure of a 3D print, and its selection has a profound impact on the overall model’s strength, weight, and material usage. Different patterns create varying densities and load distribution characteristics. Understanding these differences allows for the selection of an infill pattern that best suits the intended application of the printed part.Here’s a look at the impact of common infill patterns on model robustness:

- Grid: This is a common and relatively strong pattern. It consists of horizontal and vertical lines forming a grid. It offers good strength in two axes but can be less efficient for isotropic strength (strength in all directions).

- Gyroid: The gyroid pattern is a complex, tri-helical structure. It is known for its excellent strength-to-weight ratio and its ability to distribute stress evenly in all directions, making it ideal for parts that experience complex loading. It also tends to be more flexible than grid patterns.

- Cubic: This pattern creates a lattice of cubes. It provides good strength, particularly in compression, and is often a good balance between strength and print time. It can be further optimized with variations like cubic subdivision, which increases the density of the internal structure.

- Honeycomb: While visually appealing and offering good strength for its weight, the honeycomb pattern’s open structure can sometimes lead to issues with layer adhesion and can be more prone to crushing under direct impact compared to more solid infill patterns.

- Lines: The simplest infill pattern, consisting of parallel lines. It is fast to print and uses less material but offers minimal strength, especially in shear or bending forces. It is generally not recommended for load-bearing applications.

For maximum strength, patterns like Gyroid, Cubic, or a high-density Grid are generally preferred. The choice between them may depend on the specific stress the part will encounter. For example, if the part will be primarily compressed, Cubic might be superior, while for parts experiencing multi-directional forces, Gyroid is often the best choice.

Effective Utilization of Support Structures

Support structures are temporary aids printed alongside the model to prevent overhangs and bridges from collapsing during the printing process. Their effective use is crucial not only for the successful completion of a print but also for the final strength of the model, especially in areas where overhangs or complex geometries are present. Improperly designed or placed supports can lead to weak points or surface imperfections that compromise structural integrity.To utilize support structures effectively for enhanced strength:

- Enable Supports Judiciously: Only enable supports for features that genuinely require them. Over-reliance on supports can introduce unnecessary interfaces between the model and the support material, potentially weakening the final part.

- Select Support Type: Most slicers offer different support types, such as ‘Normal’ (tree-like structures) and ‘Tree’ (branching structures). Tree supports can be more efficient and easier to remove, often leaving a cleaner surface finish. However, for very critical overhangs where maximum support is needed, ‘Normal’ supports might offer more stability.

- Adjust Support Overhang Angle: This setting determines at what angle overhangs will start receiving support. A lower angle (e.g., 45 degrees) means more support will be generated. For structurally critical parts, consider lowering this angle to ensure even minor overhangs are adequately supported.

- Optimize Support Density and Pattern: Support density directly impacts how much material is used and how strong the support is. Higher density supports provide more stability but are harder to remove. The support pattern (e.g., grid, lines) also affects its strength and ease of removal. A balance is needed to ensure the support is strong enough to hold the overhang but removable without damaging the model.

- Set Support Z Distance: This is the vertical gap between the model and the support structure. A smaller Z distance (e.g., 0.1mm to 0.2mm) can improve the surface finish of the overhang but makes supports harder to remove. A larger distance makes removal easier but can lead to a rougher surface. For strength, a minimal Z distance that still allows for clean removal is ideal, as it provides better support to the overhang.

- Consider Support Interface Layers: Some slicers allow for denser, more solid layers at the interface between the support and the model. Enabling these can significantly improve the surface quality of the overhang and provide a more robust connection, indirectly contributing to the model’s overall strength in that area.

High-Strength Print Settings Profile Template

Creating a dedicated settings profile for high-strength prints ensures consistency and allows for quick application of optimized parameters. This template Artikels key settings to consider. Remember to adjust these based on your specific printer, filament, and the intended application of the part.

| Parameter | Recommended Setting for Strength | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Layer Height | 0.12mm – 0.16mm | Smaller layers improve adhesion and surface finish. |

| Print Speed (Overall) | 30mm/s – 50mm/s | Slower speeds allow for better layer fusion. |

| Outer Wall Speed | 20mm/s – 30mm/s | Crucial for surface integrity and preventing delamination. |

| Infill Density | 75% – 100% | Higher density significantly increases strength. |

| Infill Pattern | Gyroid, Cubic, or Grid | Gyroid for isotropic strength, Cubic for compression, Grid for balanced strength. |

| Wall Line Count (Perimeters) | 4 – 6+ | More walls drastically increase strength and reduce infill dependency. |

| Top/Bottom Layers | 5 – 8+ | Ensures solid surfaces and prevents infill showing through. |

| Print Temperature | Material-specific (often +5-10°C higher than standard) | Slightly higher temperature can improve layer adhesion. |

| Retraction Distance & Speed | Optimized for material (e.g., 5-7mm at 40-50mm/s) | Minimizes stringing, which can affect surface quality and weak points. |

| Cooling Fan Speed | 30%

|

Reduced cooling can improve layer adhesion, especially for materials like ABS. PLA might require some cooling. |

| Support Overhang Angle | 40° – 50° | Provides support for more challenging overhangs. |

| Support Density | 20% – 30% | Balance between support strength and ease of removal. |

| Support Z Distance | 0.1mm – 0.2mm | Aims for good surface finish and strong support connection. |

| Support Interface Layers | Enabled (e.g., 2-3 layers) | Improves surface quality and connection strength. |

Advanced Slicing Techniques and Strategies

Moving beyond fundamental settings, advanced slicing techniques unlock significant improvements in 3D print strength and efficiency. These methods leverage sophisticated software features and a deeper understanding of the printing process to optimize structural integrity and material usage.

By thoughtfully applying these strategies, you can create parts that are not only stronger but also lighter and more cost-effective.

Hollow Structures with Internal Bracing

Creating hollow structures with integrated internal bracing is a powerful method for achieving exceptional strength-to-weight ratios. This approach mimics the design principles found in nature and aerospace engineering, where complex internal geometries provide support without adding excessive mass.To implement this, specialized slicing software features often allow for the definition of internal support structures that are printed as part of the model itself.

These can range from simple internal walls and crossbeams to more complex lattice or honeycomb infills that are strategically placed within the hollow sections. The key is to ensure these internal elements are oriented to effectively resist the anticipated stress directions. For instance, a beam designed to withstand bending loads would benefit from internal bracing oriented perpendicular to the bending axis.

Varying Infill Density and Pattern

The strategic variation of infill density and pattern within different sections of a single model offers a nuanced approach to optimizing strength and material consumption. Not all parts of a model experience the same level of stress, and therefore, do not require the same level of internal support.Consider a bracket that is bolted to a surface at one end and supports a load at the other.

The area around the bolt holes and the section directly supporting the load would benefit from a higher infill density and a stronger infill pattern, such as gyroid or cubic. Conversely, sections of the bracket that are primarily aesthetic or experience minimal stress can be printed with a lower infill density and a lighter pattern like lines or grid, significantly reducing print time and material usage.

This targeted approach ensures that material is used where it is most needed, leading to a more efficient and robust print.

Multi-Material Printing for Hybrid Structures

Multi-material printing opens up possibilities for creating hybrid structures that leverage the unique properties of different filaments to enhance localized strength. By strategically depositing different materials in specific areas, you can create parts with tailored performance characteristics.For example, a component that requires high tensile strength in one area and impact resistance in another can be printed with a strong, rigid filament for the tensile section and a more flexible, impact-absorbing filament for the other.

Slicing software that supports multi-material printing allows for the precise definition of these material zones, often through color changes or dedicated toolpath generation. This technique is particularly valuable for functional prototypes and end-use parts where specific performance requirements dictate the use of specialized materials in a single, integrated component.

Orienting Models for Stress Alignment

The orientation of a model on the print bed is a critical factor in determining its final strength, as it dictates the direction of layer lines relative to anticipated stress. Fused deposition modeling (FDM) prints are inherently anisotropic, meaning their strength varies depending on the direction of applied force relative to the layer adhesion.To maximize strength, layer lines should be aligned with the expected stress directions.

If a part is expected to experience tensile stress along its length, orienting it so that the layers run parallel to that length will result in a much stronger part. Conversely, orienting it so that the stress is applied perpendicular to the layer lines can lead to delamination and premature failure. This requires careful analysis of the part’s function and how forces will be applied.

For instance, a hook designed to bear weight vertically would be strongest if its layers are oriented horizontally, allowing the tensile forces to pull along the layers rather than across them.

Using Shell Settings for Stronger Outer Surfaces

Shell settings, often referred to as wall thickness or perimeters, play a crucial role in creating stronger outer surfaces for 3D printed parts. The outer shell provides the primary structural integrity and resistance to external forces, and its design significantly impacts the overall durability of the print.Increasing the number of shells or the wall thickness directly reinforces the outer boundary of the model.

This is particularly effective for parts that are subjected to abrasion, impact, or bending. For instance, a container designed to hold heavy objects might benefit from having 4-6 shells to ensure the outer walls can withstand the pressure without deforming or cracking. Some slicing software also offers options for variable wall thickness, allowing you to increase the shell density in areas prone to higher stress or wear, further optimizing strength and material usage.

Testing and Iteration for Optimal Strength

Having meticulously prepared your model and configured your slicing software, the next crucial phase involves rigorously testing your creations to ensure they meet the desired strength benchmarks. This section will guide you through establishing a robust testing methodology, interpreting the results of these tests, and employing an iterative approach to refine your slicing strategies for maximum structural integrity.The process of optimizing a sliced model for strength is not a one-time event but a continuous cycle of testing, analysis, and refinement.

By systematically evaluating how your printed parts withstand stress, you can pinpoint weaknesses and make informed adjustments to your slicing parameters, progressively enhancing the durability of your prints.

Stress Testing Methodology for Sliced Models

To effectively evaluate the performance of sliced models, a structured approach to stress testing is essential. This methodology should aim to simulate real-world load-bearing conditions as closely as possible, allowing for quantifiable measurements of strength and identification of failure points.A basic stress testing protocol can involve the following steps:

- Preparation of Test Specimens: Print identical models using the established slicing settings. It is advisable to print multiple specimens to account for inherent variations in the printing process and to ensure the reliability of your test results.

- Selection of Test Fixtures: Design or acquire appropriate fixtures that can apply controlled loads to the specimens. These fixtures should mimic the intended application of the final part. For example, a tensile test might require a grip that can pull the specimen apart, while a compression test would need a flat surface to apply force.

- Application of Load: Apply a controlled and increasing load to the test specimen. This can be achieved using a universal testing machine, a calibrated weight system, or even a DIY setup with a load cell. The rate at which the load is applied is also a critical factor; slow, steady application is generally preferred for static strength testing.

- Measurement of Deformation and Failure: Monitor the specimen for any signs of deformation, such as bending or stretching, as the load increases. Record the load at which significant deformation occurs and, crucially, the load at which the specimen fails (e.g., breaks, cracks, or delaminates).

- Data Recording: Meticulously record all relevant data, including the applied load, any observed deformation, and the failure load for each test specimen. Note the environmental conditions during testing, such as temperature and humidity, as these can influence material properties.

Identifying and Interpreting Failure Points

After conducting stress tests, the ability to accurately identify where and how a model fails is paramount to understanding its weaknesses. This analysis forms the foundation for informed adjustments to your slicing parameters.Techniques for identifying areas of failure include:

- Visual Inspection: Carefully examine the fractured surfaces of the failed specimen. Look for patterns such as delamination between layers, brittle fracture across infill structures, or shear failure along specific orientations.

- Microscopic Examination: For more detailed analysis, a microscope can reveal finer details of the fracture mechanism, such as voids, incomplete fusion between extruded lines, or the presence of internal defects.

- X-ray Computed Tomography (CT) Scanning: This advanced technique can reveal internal defects that are not visible on the surface, such as voids, air bubbles, or inconsistencies in infill density, which can act as stress concentrators.

Interpreting the results involves correlating the observed failure modes with the slicing settings used. For instance:

- Delamination between layers: This often indicates insufficient layer adhesion, which can be addressed by increasing print temperature, reducing print speed, or optimizing cooling fan settings.

- Brittle fracture of infill: This suggests that the infill pattern or density might not be providing adequate support, or that the material itself is too brittle. Adjusting infill percentage, pattern, or exploring different filament types could be beneficial.

- Cracking at corners or sharp edges: These areas are prone to stress concentration. Improving wall thickness, adding fillets, or adjusting cooling to prevent warping can help.

A common observation in stress testing is that failures often initiate at points of stress concentration, which can be exacerbated by printing defects. For example, a small void within a wall can act as a crack initiation site under load.

Iterative Modification of Slicing Settings

The strength optimization of a 3D printed part is an iterative journey. Based on the insights gained from stress testing and failure analysis, you will repeatedly adjust your slicing parameters to enhance durability.The iterative process typically follows these steps:

- Analyze Test Results: Review the data and failure observations from the previous test cycle. Identify the primary causes of failure.

- Formulate Hypotheses: Based on the analysis, hypothesize which slicing settings are most likely to address the identified weaknesses. For example, if delamination is the issue, you might hypothesize that increasing the nozzle temperature by 5°C will improve layer adhesion.

- Modify Slicing Settings: Make targeted changes to one or a few slicing parameters. It is generally advisable to change only one significant parameter at a time to isolate its effect. For example, adjust layer height, wall thickness, infill density, print speed, or temperature.

- Reprint and Retest: Print new test specimens using the modified settings and repeat the stress testing procedure.

- Compare Results: Compare the results of the new tests with the previous ones. Did the changes improve the strength or change the failure mode in a desirable way?

- Repeat: Continue this cycle of analysis, modification, and testing until the desired strength is achieved or further improvements become marginal.

This systematic approach ensures that each modification is data-driven, leading to a more robust and optimized final product.

Documenting Successful Slicing Configurations

To leverage your efforts and ensure consistency, maintaining a comprehensive record of successful slicing configurations is vital. This documentation serves as a valuable reference for future projects and troubleshooting.A plan for documenting successful configurations should include:

- Project Identification: Clearly label each configuration with the project name, part name, and the intended application or strength requirement.

- Slicing Software Version: Record the specific version of the slicing software used, as settings can sometimes behave differently across versions.

- Material Details: Document the filament type, brand, color, and any specific material properties (e.g., tensile strength, Young’s modulus) that were provided by the manufacturer.

- Key Slicing Parameters: List all relevant slicing settings, including layer height, wall thickness, top/bottom layers, infill density and pattern, print speed for different features (walls, infill, top/bottom), nozzle and bed temperatures, cooling fan speed, retraction settings, and any advanced settings like coasting or ironing.

- Test Results: Summarize the outcomes of the stress tests performed with this configuration, including average failure load, observed failure modes, and any qualitative observations about the print quality.

- Iteration Notes: Briefly describe the modifications made from previous configurations and the rationale behind them, along with the observed impact of those changes.

- Print Settings Snapshot: Consider taking screenshots of the slicing software interface with the final successful settings displayed, as this provides a visual record.

This detailed record-keeping allows for quick replication of successful settings and provides a knowledge base for tackling new design challenges.

Comparative Analysis of Slicing Approaches

To gain a deeper understanding of how different slicing strategies impact strength, a comparative analysis through simulated load-bearing scenarios is highly effective. This involves testing variations in key slicing parameters and observing their performance under identical stress conditions.Consider the following simulated load-bearing scenarios for comparison:

| Slicing Approach/Parameter Varied | Simulated Load Scenario | Expected Outcome & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Increased Wall Thickness (e.g., 4 walls vs. 2 walls) | Tensile stress test on a beam specimen. | Higher Failure Load: Increased wall thickness directly enhances the cross-sectional area resisting tensile forces, leading to greater strength. This is analogous to using thicker beams in construction for increased load capacity. |

| Higher Infill Density (e.g., 80% vs. 20%) | Compression test on a cylindrical post. | Higher Failure Load: A denser infill provides more internal support, distributing the compressive load more effectively and reducing the likelihood of buckling or crushing. This is similar to how a solid cylinder is stronger in compression than a hollow one. |

| Infill Pattern (e.g., Gyroid vs. Grid) | Impact resistance test on a flat plate. | Improved Energy Absorption: Gyroid infill patterns are known for their ability to distribute stress and absorb impact energy more uniformly than simpler grid patterns, potentially leading to less localized failure. This is akin to the crumple zones in vehicles designed to absorb impact energy. |

| Layer Height (e.g., 0.1mm vs. 0.3mm) | Bending stress test on a cantilever beam. | Potentially Higher Strength (with caveats): Thinner layers generally lead to better layer adhesion due to increased surface contact and heat retention. However, excessively thin layers can increase print time and may not always translate to superior strength if other factors like print speed or temperature are not optimized. |

| Print Speed (e.g., 40mm/s vs. 80mm/s) | Shear stress test on a joint. | Higher Failure Load at Slower Speed: Slower print speeds allow for better material flow, increased layer adhesion, and reduced internal stresses from rapid cooling. This is critical for ensuring the integrity of the bonds between extruded lines, especially under shear forces. |

By conducting these comparative analyses, you can quantitatively demonstrate the impact of various slicing strategies on the mechanical performance of your 3D printed parts, guiding your decisions for future designs.

Ultimate Conclusion

In essence, mastering How to Slice a Model for Maximum Strength is a multifaceted endeavor that blends scientific understanding with practical application. By diligently considering material characteristics, optimizing geometry, fine-tuning slicing parameters, and embracing an iterative testing process, you can consistently produce 3D printed parts that not only meet but exceed expectations for durability and performance. This comprehensive approach empowers you to create stronger, more reliable models for a wide array of applications.