Embarking on the journey of 3D modeling from the physical world requires a foundational understanding of precise measurement. This guide will illuminate the essential principles, tools, and techniques necessary to accurately capture the dimensions and forms of real-world objects, transforming tangible items into digital assets.

We will delve into the critical importance of accurate measurements, explore the diverse array of tools available from simple tapes to advanced scanners, and dissect effective methods for measuring various object geometries. Furthermore, we will address the crucial aspects of scale, unit consistency, data organization, and tackle advanced considerations for a comprehensive approach to object measurement.

Understanding the Fundamentals of Real-World Measurement for 3D

Embarking on the journey of 3D modeling from real-world objects hinges on a solid understanding of measurement principles. Accurate data capture is the bedrock upon which faithful digital replicas are built, ensuring that the virtual object mirrors its physical counterpart in form, size, and proportion. Without this foundational accuracy, the subsequent stages of modeling, texturing, and rendering can lead to disappointing results, misrepresentations, and ultimately, a failure to achieve the desired outcome.

This section will guide you through the essential concepts and considerations for effective real-world measurement.The fidelity of your 3D model is directly proportional to the accuracy of your initial measurements. Whether you are digitizing a historical artifact, a product prototype, or an architectural element, precise dimensions are paramount. These measurements dictate the scale, proportions, and overall geometry of your digital asset, influencing its usability in various applications, from game development and architectural visualization to product design and virtual reality experiences.

Primary Dimensions for Capturing Physical Form

When approaching a physical object for 3D modeling, it’s crucial to identify and record the key dimensions that define its shape. These primary measurements provide the skeletal framework for your digital model, ensuring that its overall form is accurately represented.The fundamental dimensions typically required include:

- Length: The longest dimension of an object, usually measured from end to end.

- Width: The dimension measured across the object, perpendicular to its length.

- Height: The vertical dimension of an object, measured from its base to its highest point.

- Depth: Similar to width, but often used for flatter objects or to describe how far an object extends from a surface or front to back.

- Diameter: For circular or cylindrical objects, this is the distance across the center from one side to the other.

- Radius: Half of the diameter, measured from the center to the edge of a circular object.

- Circumference: The distance around the outer edge of a circular or cylindrical object.

- Angles: Crucial for defining the relationships between different planes and surfaces, especially for complex shapes or beveled edges.

- Curvature: For objects with curved surfaces, understanding the radius of curvature at different points is vital for accurate representation.

Principles of Scale and Proportion

Scale and proportion are interconnected concepts that are fundamental to translating a physical object into a digital representation. Scale refers to the size of the digital model relative to the real-world object, while proportion describes the relationship between the different parts of the object.

“Accuracy in scale ensures that a digital asset maintains its true-world size, critical for applications like architectural walkthroughs or fitting virtual furniture into a real room.”

Maintaining correct proportions is equally important. If the length of a chair is accurately measured but its width is proportionally incorrect, the resulting 3D model will appear distorted and unrealistic, even if individual measurements are technically correct. The goal is to capture not just the absolute sizes but also the harmonious relationships between these sizes.

Common Pitfalls in Initial Measurement Approaches

Approaching a physical object for measurement without careful consideration can lead to significant errors that are difficult to rectify later in the modeling process. Being aware of these common pitfalls can help you avoid them.Key challenges to anticipate and overcome include:

- Inconsistent Units: Mixing units of measurement (e.g., inches and centimeters) within a single project can lead to drastic scaling errors. Always establish a consistent unit system from the outset.

- Ignoring Object Complexity: Assuming a simple shape when the object has intricate details, subtle curves, or hidden features can result in an incomplete or inaccurate model. Thoroughly inspect the object before measuring.

- Insufficient Measurement Points: For complex or organic shapes, a few linear measurements may not be enough. You may need to take measurements at multiple points or use specialized techniques to capture curvature and irregular surfaces.

- Environmental Factors: Lighting conditions, the object’s surface reflectivity, and the presence of obstructions can all affect the accuracy of your measurements, especially when using certain tools.

- Tool Limitations: Not all measuring tools are suitable for every object or level of detail. Using a tape measure for a tiny, intricate component will yield less accurate results than using calipers.

- Observer Bias: Subconsciously rounding measurements or making assumptions based on perceived proportions can introduce inaccuracies. Strive for objective and precise readings.

Essential Tools and Equipment for Object Measurement

To accurately capture the dimensions and form of real-world objects for 3D modeling, having the right tools is paramount. The selection of equipment often depends on the object’s size, complexity, and the desired level of detail and accuracy for your 3D model. This section Artikels the essential tools, categorizing them by their precision, and discusses their respective advantages and applications.A well-equipped measurement kit can significantly streamline the 3D modeling process, ensuring that your digital representations are faithful to their physical counterparts.

Understanding the capabilities and limitations of each tool will help you make informed decisions about your workflow and achieve optimal results.

Categorization of Measurement Tools by Precision Level

Measurement tools can be broadly categorized based on the accuracy they provide, ranging from moderate to very high precision. This classification helps in selecting the appropriate tool for specific tasks, ensuring that the required level of detail is met without overspending on unnecessary precision.

- Low to Moderate Precision: These tools are suitable for general measurements and larger objects where minute inaccuracies are acceptable. They are typically easy to use and widely available.

- High Precision: Essential for capturing intricate details and ensuring accurate proportions, these tools offer finer measurements and are crucial for detailed modeling.

- Very High Precision: These advanced tools are often used for professional applications requiring the utmost accuracy, such as reverse engineering or scientific documentation.

Manual vs. Digital Measuring Tools

The choice between manual and digital measuring tools involves a trade-off between cost, ease of use, and precision. Both have their strengths and weaknesses, and often, a combination of both is ideal for comprehensive object measurement.Manual measuring tools, such as measuring tapes and rulers, are generally more affordable and do not require batteries or power sources. They are intuitive to use for basic linear measurements.

However, they can be prone to parallax error and require careful reading, which can affect accuracy, especially for complex shapes or when measuring long distances. Digital tools, on the other hand, offer greater precision and often provide instant readouts, reducing the chance of human error in reading the measurement. Many digital calipers and rulers have features like data output, which can be directly imported into software, further enhancing efficiency.

The primary disadvantage of digital tools is their cost and reliance on power.

Functionality and Application of Laser Distance Meters

Laser distance meters, also known as laser rangefinders, are invaluable tools for measuring distances quickly and accurately, especially for larger objects or spaces. They work by emitting a laser beam that reflects off a target surface and returns to the device. The time it takes for the beam to travel is then used to calculate the distance.

Laser distance meters utilize the principle of time-of-flight measurement, where the speed of light is a known constant. The formula used is Distance = (Speed of Light × Time of Flight) / 2. The division by two accounts for the round trip of the laser beam.

Their applications in 3D modeling are diverse. For measuring the overall dimensions of a room or a large object like a car, a laser distance meter can provide rapid and precise readings, significantly faster than a traditional tape measure. Some advanced models can also measure angles and perform area or volume calculations, making them versatile for initial object assessment and data collection.

While they excel at linear measurements, they do not capture surface geometry, meaning they are best used in conjunction with other tools for detailed surface scanning.

Beginner’s Equipment Checklist for Object Measurement

For individuals new to 3D modeling and real-world object measurement, a basic yet effective set of tools can lay a strong foundation. This checklist focuses on accessibility, versatility, and the ability to capture fundamental measurements.

- Measuring Tape (at least 5 meters): For general linear measurements of larger objects and spaces.

- Ruler (30 cm or 12 inches): For smaller, more detailed measurements and cross-referencing.

- Digital Calipers (vernier or digital): Essential for precise measurements of smaller parts, diameters, and thicknesses. Look for a range of at least 0-150mm.

- Protractor: To measure angles, which are crucial for replicating the correct geometry of objects with non-rectangular forms.

- Smartphone with a reliable camera: For taking reference photos and, with the right apps, for photogrammetry (though this is a more advanced technique).

- Notebook and Pen/Pencil: For recording all measurements and observations.

Recommended Tools for Object Measurement in a Table Format

The following table provides a curated list of recommended tools, detailing their primary use, typical precision level, and specific examples of how they are applied in the context of 3D modeling.

| Tool | Primary Use | Precision Level | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measuring Tape | Linear Distances (larger objects) | Moderate (e.g., ±1-3 mm per meter) | Measuring the length, width, and height of a piece of furniture. |

| Ruler | Linear Distances (smaller objects) | Moderate to High (e.g., ±0.5-1 mm) | Measuring the dimensions of a book or a component on a circuit board. |

| Calipers (Digital/Vernier) | Precise Dimensions (internal, external, depth) | High (e.g., ±0.02-0.05 mm) | Measuring the diameter of a bottle cap, the thickness of a smartphone case, or the depth of a recess. |

| Laser Distance Meter | Long-Distance Linear Measurements | Moderate to High (e.g., ±1-2 mm over 10 meters) | Measuring the dimensions of a room for architectural modeling or the length of a vehicle. |

| 3D Scanner (Handheld) | Surface Geometry Capture | Varies (High to Very High, e.g., ±0.1-1 mm depending on scanner and object) | Scanning a complex statue, a detailed architectural facade, or a custom-made part for reverse engineering. |

| Protractor | Angle Measurement | Moderate (e.g., ±0.5-1 degree) | Measuring the angle of a bevel on a piece of wood or the tilt of a roofline. |

Techniques for Measuring Various Object Geometries

Accurately capturing the shape and dimensions of real-world objects is fundamental to creating faithful 3D models. The approach taken will vary significantly depending on the object’s complexity, ranging from simple geometric primitives to highly intricate forms. Understanding these diverse techniques ensures that you can select the most appropriate method for any given object.

Measuring Simple Geometric Shapes

For objects that conform to basic geometric definitions, direct measurement with common tools is highly effective. These shapes are predictable, allowing for straightforward data collection.

Cubes and Rectangular Prisms

The key dimensions to measure are length, width, and height. For a perfect cube, all three measurements will be identical. For rectangular prisms, these values will differ. Ensure measurements are taken along the edges and at right angles.

Spheres

Measuring a sphere involves determining its diameter. This can be done by placing the sphere between two parallel surfaces (like two blocks of wood) and measuring the distance between them, or by using calipers to span the widest part of the sphere. The radius is half the diameter.

Cylinders

For cylinders, two primary measurements are needed: the diameter (or radius) of the circular base and the height. The diameter is measured across the widest part of the circular end, and the height is the perpendicular distance between the two circular bases.

Capturing Curved Surfaces and Irregular Forms

Objects with curved surfaces and non-standard shapes require more nuanced measurement techniques to ensure accuracy.

Using Flexible Measuring Tapes and Curves

For gentle curves, a flexible tailor’s measuring tape can be draped along the contour to capture its length. For more complex or tighter curves, specialized tools like flexible rulers or even string that can then be measured against a standard ruler are useful. When measuring curved surfaces, it’s important to take multiple readings at different points to understand the curvature’s variation.

Employing Calipers for Complex Curves

While calipers are excellent for linear measurements, they can also be used to measure the diameter of curved sections at specific points. For highly irregular forms, a combination of direct measurements and detailed photographic documentation from multiple angles is crucial.

Measuring Objects with Intricate Details or Fine Features

Objects with fine details, such as engravings, small protrusions, or delicate filigree, present unique challenges.

High-Precision Tools for Fine Features

For very small or intricate details, precision tools become indispensable. Digital calipers offer higher accuracy than traditional ones and can measure down to fractions of a millimeter. For extremely fine features, a microscope with a reticle (a scale etched onto a lens) can be used to measure dimensions directly. Macro photography can also be used to capture these details, allowing for measurement in post-processing.

Detailed Photogrammetry for Intricate Surfaces

When dealing with complex surface details, photogrammetry, which uses a series of overlapping photographs, can reconstruct highly detailed geometry. The software analyzes the parallax between images to derive depth information, effectively capturing fine surface textures and intricate patterns.

Comparing Photogrammetry with Structured Light Scanning

Both photogrammetry and structured light scanning are powerful non-contact methods for capturing object geometry, each with its strengths and weaknesses.

Photogrammetry

This technique reconstructs 3D models from a collection of 2D photographs taken from various angles.

- Pros: Relatively low equipment cost (standard cameras), excellent for capturing texture and color, can be used on very large or small objects, and requires minimal object preparation.

- Cons: Can be sensitive to lighting conditions, requires significant processing power and time, accuracy can be affected by featureless surfaces or reflective materials, and can struggle with highly transparent or translucent objects.

Structured Light Scanning

This method projects a known pattern of light (e.g., stripes or grids) onto an object and uses cameras to observe how the pattern deforms. This deformation is then analyzed to calculate the object’s 3D shape.

- Pros: High accuracy and resolution, fast data acquisition, less sensitive to ambient lighting than photogrammetry, and can capture fine details effectively.

- Cons: Higher equipment cost, limited by the scanner’s field of view and working distance, can struggle with dark, shiny, or transparent surfaces without preparation (e.g., using a matte spray), and typically captures geometry without color information.

The choice between them often depends on the required accuracy, the object’s material properties, available budget, and the desired level of detail for texture.

Step-by-Step Procedure for Measuring a Common Household Item: A Chair

Measuring a chair involves a systematic approach to capture its overall dimensions and any specific features.

Step 1: Identify key dimensions

Before starting, mentally or physically note the most critical dimensions needed for your 3D model. For a chair, these typically include:

- Overall height (from floor to the highest point, usually the backrest).

- Seat height (from floor to the top of the seat).

- Seat width and depth.

- Armrest height and width (if applicable).

- Leg thickness and spacing.

- Backrest height and width.

Step 2: Use a measuring tape for overall dimensions

Employ a standard retractable measuring tape to capture the primary dimensions.

- Measure the overall height, width (across the widest points, including arms if present), and depth (front to back).

- Measure the seat dimensions (width and depth) and the seat height from the floor.

- Record the height of the armrests from the seat and their width.

- Measure the height and width of the backrest.

It’s advisable to take multiple measurements for each dimension and average them to account for slight inconsistencies in the object or the measuring tape.

Step 3: Employ calipers for precise measurements of dowels or screws

For smaller, more precise elements like the thickness of chair legs, dowels, or the heads of visible screws, calipers are ideal.

- Use the jaws of the calipers to measure the diameter of cylindrical legs or dowels.

- Measure the width of square or rectangular legs.

- If measuring screw heads for detail, ensure the calipers capture the diameter or the head’s largest dimension.

Digital calipers are particularly useful here for their accuracy.

Step 4: Note any curvatures or angled components

Observe and record any deviations from straight lines or perfect right angles.

- Assess the backrest for any curvature and measure its arc or contour if significant.

- Check if the legs are angled outwards or inwards and record the angle using a protractor or by measuring the displacement at the top and bottom.

- Note any rounded edges or chamfers on the wood or frame, and measure their radius or bevel.

- If the seat has a contoured shape, measure its depth at different points or its highest and lowest points.

Detailed notes and sketches, supplemented by photographs, are invaluable for capturing these complex geometric aspects accurately.

Dealing with Scale, Units, and Data Organization

Ensuring accuracy and consistency in your 3D modeling workflow hinges on meticulous attention to scale, units, and the organization of your collected data. Without a robust system for managing these elements, even the most precise measurements can lead to skewed models and frustrating rework. This section will guide you through establishing a solid foundation for handling these critical aspects.The foundation of any successful 3D modeling project begins with understanding and correctly applying units of measurement.

Inconsistent units can lead to significant discrepancies in your final model, making it difficult to integrate with other assets or use in real-world applications. Therefore, maintaining a singular, clearly defined unit throughout your entire measurement and modeling process is paramount.

Establishing a Reference Scale

Before you begin taking any measurements, it is crucial to establish a clear reference scale. This reference acts as your anchor, ensuring all subsequent measurements are taken and interpreted in the same context. Without this, you risk introducing errors from the outset.A common and effective method for establishing a reference scale is to use an object of known dimensions. This could be a standard ruler, a calibration cube, or even a commonly found item like a credit card, whose dimensions are universally recognized.

When you begin measuring your target object, you will also measure this reference object. This allows you to verify your measurement tool’s accuracy and to later confirm the scale of your collected data. For instance, if you are using a ruler and measuring a credit card, and your ruler consistently shows the credit card as slightly longer than its actual 85.6 mm, you have identified a potential calibration issue with your tool or your technique.

Documenting and Organizing Collected Measurement Data

Effective documentation and organization are as vital as the measurements themselves. A well-organized dataset not only prevents confusion but also streamlines the 3D modeling process. It allows you to quickly access the information you need and to cross-reference details efficiently.Best practices for data organization include:

- Using a consistent naming convention for your files and entries.

- Creating a dedicated folder structure for each project or object.

- Employing a digital spreadsheet or a dedicated note-taking application for recording data.

- Taking photographs of the object from multiple angles, annotating them with key measurements.

- Keeping a logbook or digital journal of your entire measurement process, including any challenges encountered.

Potential Issues Arising from Unit Mismatches and Solutions

Unit mismatches are a frequent source of errors in 3D modeling, especially when working with data from various sources or when transitioning between different software. For example, a model designed in millimeters might be imported into software that defaults to inches, leading to a drastically scaled-up or scaled-down object.The primary solution to unit mismatches is strict adherence to a single unit system throughout your workflow.

If you must work with different unit systems, meticulous conversion and verification are essential at every step.

- Identify the target unit: Before starting, decide on the primary unit system for your 3D model (e.g., millimeters, centimeters, meters, inches, feet).

- Convert early and often: If your measurement tools or source data are in different units, convert them to your target unit as soon as possible.

- Use conversion tools: Utilize online converters or built-in functions within your modeling software to perform conversions accurately.

- Verify dimensions: After importing or transferring data, always double-check critical dimensions to ensure they have been converted correctly.

Template for Recording Object Measurements

A standardized template for recording object measurements ensures that all necessary information is captured consistently. This structured approach makes data retrieval and interpretation straightforward.Here is a comprehensive template that can be adapted for various objects:

Object Name: [e.g., Coffee Mug]

Date Measured: [e.g., 2023-10-27]

Measured By: [Your Name/Identifier]

Measurement Tool(s) Used: [e.g., Digital Caliper, Tape Measure, Laser Distance Meter]

Reference Scale Used: [e.g., Standard Ruler, Known Object Dimension]Overall Dimensions:

Overall Height: [value] [unit]

Overall Width: [value] [unit]

Overall Depth: [value] [unit]Key Feature Dimensions:

Handle Diameter: [value] [unit]

Base Diameter: [value] [unit]

Lip Thickness: [value] [unit]

Wall Thickness: [value] [unit]Curvature/Irregularities:

Radius of curvature for [specific area]: [value] [unit]

Angle of [specific feature]: [value] degreesNotes: [e.g., Slight curve on the base, handle is not perfectly circular, texture details to consider]

Advanced Measurement Considerations and Best Practices

Moving beyond the fundamental tools and techniques, this section delves into more complex scenarios and offers strategies to ensure the highest level of accuracy and detail in your real-world measurements for 3D modeling. Addressing challenges and employing refined methodologies will significantly enhance the fidelity of your digital representations.Mastering advanced measurement techniques requires a keen understanding of material properties and environmental factors.

This section provides practical solutions for common obstacles encountered when capturing the geometry of real-world objects, ensuring your 3D models accurately reflect their physical counterparts.

Measuring Transparent or Reflective Objects

Transparent and highly reflective surfaces pose a significant challenge for most optical measurement systems, including standard 3D scanners. Light can pass through transparent objects or bounce off reflective surfaces unpredictably, leading to noisy data, missing information, or inaccurate readings.To overcome these difficulties, several workarounds can be employed. For transparent objects, applying a temporary, thin coating of a non-toxic, easily removable material such as a matte spray or a specialized scanning powder can diffuse the light and create a surface that scanners can interpret.

This coating should be applied uniformly and thinly to avoid altering the object’s geometry. For reflective objects, similar matte sprays or even talcum powder can be used to reduce reflectivity. Alternatively, specialized scanners that utilize different wavelengths of light or structured light patterns designed to penetrate or interact differently with reflective surfaces can be considered. Polarization filters can also be effective in reducing glare from shiny surfaces.

Another approach involves taking multiple scans from various angles and using advanced registration software to fuse the data, compensating for areas that might be problematic in individual scans.

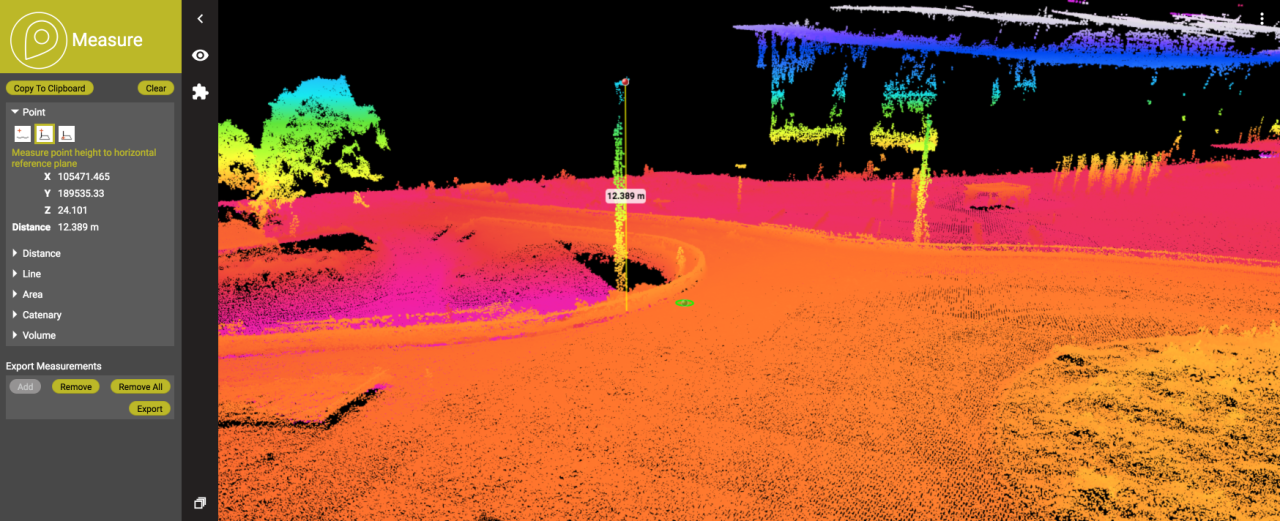

Measuring Objects In Situ Without Disassembly

Frequently, objects that require 3D modeling are either too large or too complex to be disassembled for measurement. This necessitates techniques that can capture accurate data directly in their installed or assembled state.For large structures like buildings, bridges, or industrial machinery, technologies such as terrestrial laser scanning (TLS) and drone-based photogrammetry are invaluable. TLS employs a tripod-mounted scanner that emits laser beams to capture millions of data points, creating a highly accurate point cloud of the environment.

Drone photogrammetry involves capturing a series of overlapping photographs from a drone, which are then processed using Structure-from-Motion (SfM) software to generate a dense 3D model. For more intricate mechanical parts within an assembly, portable CMMs (Coordinate Measuring Machines) or articulated measuring arms can be used to reach and measure features directly. Careful planning and setup are crucial to ensure unobstructed views and accurate positioning of the measurement equipment.

Ensuring Accuracy and Repeatability of Measurements

Achieving high accuracy and repeatability is paramount for reliable 3D modeling. This involves meticulous attention to detail throughout the measurement process and employing best practices to minimize errors.To ensure accuracy, always calibrate your measurement equipment according to the manufacturer’s specifications before each use. When using handheld devices or scanners, maintain a consistent distance and angle to the object. For photogrammetry, ensure sufficient overlap between images and use stable lighting conditions.

Repeatability is achieved by establishing a standardized workflow. This includes defining consistent reference points on the object, documenting the exact setup of your equipment, and performing multiple measurements of critical features to check for consistency. Using control points, either physical markers placed on the object or known reference points in the environment, can significantly improve the accuracy and alignment of scan data.

For critical measurements, consider using redundant measurement methods to cross-validate results.

Capturing Textures and Surface Properties

While geometric data defines the shape of an object, texture and surface properties are essential for creating photorealistic 3D models. These aspects capture the visual characteristics, such as color, roughness, and material finish.Many modern 3D scanners are equipped with integrated high-resolution cameras that can capture color information simultaneously with geometric data. This process, known as texture mapping, projects the captured photographic data onto the 3D model.

For capturing finer surface details like roughness or subtle surface imperfections, techniques like photometric stereo can be employed. This method involves taking multiple images of the object under different, controlled lighting conditions. By analyzing how light interacts with the surface in these images, software can reconstruct the surface normal map, which defines the micro-geometry and texture of the surface. Alternatively, detailed photographic documentation from various angles with consistent lighting can be used to create texture maps in post-processing using specialized texturing software.

Advanced Measurement Scenarios and Techniques

Different objects and environments present unique measurement challenges, requiring tailored approaches to achieve optimal results. Organizing these scenarios and their corresponding techniques provides a practical guide for diverse 3D modeling projects.Here is a list of advanced measurement scenarios and the appropriate techniques for each:

- Scenario: Large outdoor structure

- Technique: Total station for precise coordinate capture of key features, drone photogrammetry for comprehensive surface coverage and visual detail.

- Scenario: Small, intricate mechanical part

- Technique: High-precision digital calipers and micrometers for dimensional accuracy, optical comparator for detailed visual inspection and measurement of profiles.

- Scenario: Organic, flowing shape

- Technique: 3D scanner with high polygon count capabilities and advanced surface reconstruction algorithms, potentially augmented with structured light scanning for fine details.

- Scenario: Historical artifact with delicate surface

- Technique: Non-contact optical scanners with adjustable resolution, careful application of temporary, inert matte coatings, and meticulous handling to preserve the artifact’s integrity.

- Scenario: Complex internal geometry (e.g., engine block)

- Technique: Industrial CT scanning (Computed Tomography) to visualize and measure internal structures non-destructively.

- Scenario: Large, uniform surfaces (e.g., factory floor)

- Technique: LiDAR scanners (ground-based or airborne) for rapid, dense point cloud generation over extensive areas.

Closure

Mastering the art of measuring real-world objects is the bedrock upon which compelling 3D models are built. By understanding the fundamentals, leveraging the right tools, employing precise techniques, and diligently organizing your data, you unlock the potential to faithfully translate the physical realm into the digital space, opening doors to a universe of creative possibilities.