Delving into How to Set the Perfect Infill Density for Your Models, this introduction immerses readers in a unique and compelling narrative, offering a comprehensive guide to mastering a crucial aspect of 3D printing.

Understanding and precisely controlling infill density is fundamental to achieving optimal results in your 3D prints, influencing everything from structural integrity and weight to material consumption and print time. This exploration will demystify the process, providing clear insights and actionable strategies for every application.

Understanding Infill Density: The Foundation

Infill density is a fundamental parameter in 3D printing that dictates the amount of internal structure within a printed object. It is expressed as a percentage, where 0% represents a completely hollow model and 100% signifies a solid, fully filled object. Understanding this core concept is crucial for optimizing print time, material usage, and the mechanical properties of your 3D prints.The primary functions of infill are multifaceted, contributing significantly to the success of a 3D print.

It provides internal support for outer walls, preventing them from collapsing during the printing process, especially for models with overhangs or complex geometries. Infill also plays a vital role in determining the strength and rigidity of the final part, allowing for customization based on the intended application. Furthermore, it can influence the weight of the object and the amount of material consumed, impacting both cost and environmental footprint.

Typical Range of Infill Percentages

The commonly used range for infill percentages in 3D printing applications varies widely, catering to diverse needs. For purely aesthetic models or prototypes where structural integrity is not a primary concern, infill densities as low as 5% to 15% are often sufficient. These low densities significantly reduce print time and material consumption.For functional parts that require a balance of strength and weight, infill densities typically range from 20% to 50%.

This range offers a good compromise, providing adequate support and durability without making the object excessively heavy or costly to print.When exceptional strength, rigidity, or impact resistance is paramount, such as for end-use parts or components subjected to mechanical stress, infill densities can be increased to 60% and above, often reaching 80% or even 100% for maximum solidity. However, it’s important to note that very high infill densities can lead to significantly longer print times and increased material waste.

Factors Influencing Initial Infill Density Choice

Several key factors should be considered when making the initial determination of an appropriate infill density for your 3D model. These factors help guide the decision-making process to achieve the desired balance between material properties, print efficiency, and cost.

- Part Functionality: The intended use of the printed object is the most significant determinant. A decorative item might only need minimal infill for structural support, while a functional component requiring high tensile strength or impact resistance will necessitate a much denser infill.

- Required Strength and Rigidity: If the model needs to withstand significant loads, bending forces, or maintain a specific shape under stress, a higher infill density will be required to provide the necessary internal support and material volume.

- Weight Considerations: For applications where weight is a critical factor, such as in drone components or lightweight fixtures, a lower infill density will be preferred to minimize material usage and overall mass.

- Print Time Constraints: Denser infill patterns require more travel moves and material deposition, directly increasing the time it takes to print a model. If speed is essential, a lower infill density will be a more practical choice.

- Material Properties: Different filament materials have varying inherent strengths and flexibilities. For example, a flexible filament like TPU might require a different infill strategy compared to a rigid PLA or ABS for similar functional outcomes.

- Aesthetic Requirements: While less common, in some cases, the appearance of the infill might be visible through translucent materials or thin outer walls. In such instances, a more uniform or visually appealing infill pattern might be chosen, which can indirectly influence density selection.

The interplay of these factors allows for a tailored approach to infill density, ensuring that each 3D print is optimized for its specific purpose.

Impact of Infill Density on Model Properties

The infill density, a crucial parameter in 3D printing, significantly influences the physical characteristics of a printed object. Understanding these impacts is key to achieving the desired balance between strength, weight, print efficiency, and aesthetic quality. This section delves into how varying infill densities alter the fundamental properties of your 3D models.The interplay between infill density and a model’s performance is multifaceted.

It’s not merely about making a print stronger; it’s about optimizing it for its intended application, whether that be structural integrity, reduced material usage, or a flawless surface finish.

Mechanical Strength and Infill Density

The mechanical strength of a 3D printed object is directly correlated with its infill density. A higher infill density results in a more solid internal structure, which translates to increased resistance to forces such as tension, compression, and impact. Conversely, a lower infill density creates a more hollow interior, making the object weaker and more prone to deformation or breakage under stress.The internal lattice structure created by the infill acts as a support system for the outer walls.

As the infill density increases, the density of this support network grows, providing a more robust foundation. For instance, a part designed to bear significant load, such as a functional bracket or a mechanical component, would benefit from a higher infill density, typically ranging from 70% to 100% for maximum strength. For less critical parts or those requiring a balance of strength and weight, densities between 20% and 50% might suffice.

Infill Density and Model Weight

There is a direct and proportional relationship between infill density and the weight of a 3D printed model. As the infill density increases, more material is deposited within the internal structure of the object, leading to a heavier final print. This relationship is linear: doubling the infill density will, in most cases, approximate doubling the weight of the infill itself, assuming consistent material and print settings.Consider the application of a drone component.

If weight is a critical factor for flight performance, a lower infill density (e.g., 10-20%) would be selected to minimize mass. In contrast, a desk organizer might not have strict weight constraints, allowing for a higher infill density (e.g., 30-50%) to provide a more substantial feel and increased durability without a significant penalty.

Influence on Print Time and Material Consumption

Infill density has a substantial effect on both the time it takes to print a model and the amount of filament consumed. Higher infill densities require the 3D printer to lay down more material in a more complex pattern, significantly extending the print duration. Similarly, more material is used, increasing the overall filament cost of the print.The following table illustrates the approximate impact of infill density on print time and material consumption for a standard cube model (e.g., 100x100x100 mm) using common infill patterns like rectilinear or grid.

| Infill Density (%) | Approximate Print Time Increase (%) | Approximate Material Consumption Increase (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 100% (baseline) | 100% (baseline) |

| 20 | 120% | 120% |

| 50 | 170% | 170% |

| 80 | 250% | 250% |

| 100 | 300% | 300% |

This data demonstrates that a small increase in infill density can lead to a disproportionately larger increase in print time and material usage. For rapid prototyping or early design iterations, a lower infill density is often preferred to speed up the process and conserve resources.

Effect on Visual Appearance of Outer Surfaces

While infill density primarily affects the internal structure, it can also indirectly influence the visual appearance of the outer surfaces of a 3D printed model. In some cases, particularly with lower infill densities or translucent filaments, the infill pattern can become visible through the outer walls, creating a textured or slightly uneven surface finish.This effect is more pronounced with:

- Thin outer walls: When the shell thickness is minimal, the internal structure has a greater chance of showing through.

- Translucent or transparent filaments: The infill pattern is more easily visible through these materials.

- Certain infill patterns: Patterns with larger gaps or less uniform distribution can lead to more noticeable surface irregularities.

For models where a pristine, smooth outer surface is paramount, such as decorative items or visual prototypes, it is advisable to use a higher infill density (e.g., 50% or more) or ensure sufficient wall thickness to obscure the infill. Additionally, choosing infill patterns that create a denser internal structure, like gyroid or cubic, can also help minimize this visual bleed-through.

Determining the Ideal Infill Density for Different Applications

Selecting the appropriate infill density is a critical step in 3D printing, directly influencing a model’s strength, weight, material consumption, and print time. This section guides you through a systematic process to identify the optimal infill density for various functional requirements and common 3D printing use cases. By understanding the trade-offs involved, you can make informed decisions that align with your project’s specific needs.The process of determining ideal infill density involves a careful consideration of the intended function of the printed part.

It’s not a one-size-fits-all scenario; rather, it’s a tailored approach that balances structural integrity with other important factors. We will explore common applications and provide recommended infill density ranges, along with strategies for adjusting density for prototypes versus final production parts.

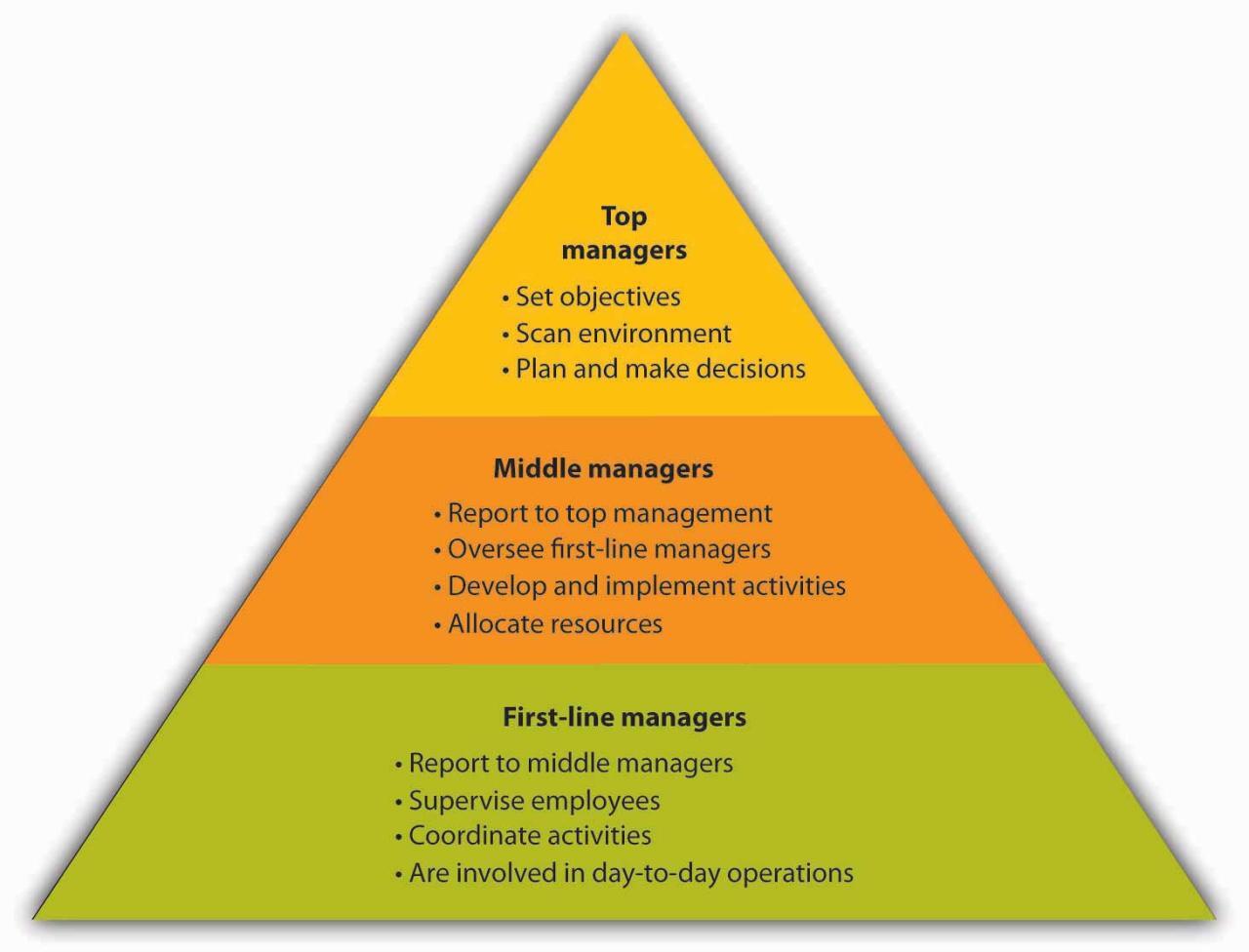

Decision-Making Process for Selecting Infill Density

To effectively determine the ideal infill density, a structured decision-making process is essential. This involves clearly defining the functional requirements of the printed object and then mapping those requirements to appropriate infill settings. The core principle is to provide sufficient strength and rigidity for the intended use without over-engineering the part, which can lead to wasted material and increased print times.The decision-making process can be broken down into the following key steps:

- Define Functional Requirements: Clearly articulate the primary purpose of the printed part. Will it be subjected to significant stress, impact, or load? Is it primarily for aesthetic display, or does it need to withstand environmental factors?

- Assess Stress and Load-Bearing Needs: Quantify, if possible, the expected forces the part will encounter. This could involve considering tensile strength, compressive strength, flexural strength, and impact resistance.

- Consider Weight and Material Constraints: Determine if weight is a critical factor, such as in aerospace or drone applications. Also, consider the cost and availability of printing materials and the impact of infill density on material consumption.

- Evaluate Print Time and Complexity: Higher infill densities generally result in longer print times. Assess if the desired strength justifies the increased printing duration and potential for print failures at higher densities.

- Prioritize Aesthetics: For purely decorative items, the infill density might be less critical for structural integrity but can still affect the surface finish if the infill pattern shows through.

- Iterative Testing and Refinement: For critical applications, it is often advisable to print test pieces with varying infill densities and subject them to the intended stresses to validate the chosen setting.

Common 3D Printing Use Cases and Recommended Infill Densities

Different applications demand varying levels of structural integrity and material efficiency. By categorizing common 3D printing use cases, we can establish sensible infill density ranges that provide a good starting point for users. These ranges are based on typical performance requirements and are intended to be adjusted based on specific design considerations and printer capabilities.Here are some common 3D printing use cases and their generally recommended infill density ranges:

- Prototypes (Functional & Visual): For prototypes that are primarily for form, fit, and visual checks, lower infill densities are often sufficient. This allows for faster printing and material savings.

- Visual Prototypes: 5-15% infill.

- Basic Functional Prototypes (low stress): 15-25% infill.

- Functional Parts (Low to Medium Stress): Parts that require some degree of strength but are not subjected to extreme forces. This could include enclosures for electronics, jigs, fixtures, or decorative items that need to be robust.

- Medium Stress Applications: 25-50% infill.

- High-Strength Functional Parts: Components that need to withstand significant mechanical stress, impact, or load-bearing. This includes mechanical parts, tools, end-use components in machinery, or items designed for repeated use.

- High Stress Applications: 50-75% infill.

- Extremely High-Strength or Rigid Parts: For applications requiring maximum rigidity and load-bearing capacity, or where parts might be subjected to extreme forces or repeated impacts.

- Maximum Strength Applications: 75-100% infill (solid).

- Lightweight Structures: When minimizing weight is paramount, while still maintaining some structural integrity, specific infill patterns like gyroid or honeycomb can be used at lower densities.

- Lightweight, Moderate Strength: 10-25% infill.

Infill Density Recommendations for Example Applications

To provide a more concrete understanding, consider the following table which Artikels example applications and their recommended infill densities. These recommendations take into account the typical stresses, load-bearing requirements, and aesthetic considerations associated with each use case. It’s important to remember that these are starting points, and actual requirements may necessitate adjustments based on specific design nuances, material properties, and the chosen infill pattern.

| Example Application | Primary Function | Recommended Infill Density Range (%) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phone Case | Protection, aesthetics | 15-30% | Impact resistance, slight flexibility, material savings. |

| Tool Handle | Ergonomics, moderate strength | 30-50% | Grip comfort, resistance to moderate forces, durability. |

| Mechanical Bracket | Load-bearing, structural support | 50-75% | Tensile strength, rigidity, resistance to bending and shear forces. |

| Drone Frame Component | Lightweight, structural integrity | 20-40% | Weight reduction, resistance to vibration and impact, stiffness. |

| Decorative Figurine | Aesthetics | 5-15% | Minimal material usage, good surface finish, no significant load-bearing. |

| Gear (low torque) | Mechanical function, moderate stress | 60-80% | Wear resistance, tooth strength, smooth operation. |

| Replacement Part (e.g., knob) | Functional replacement, moderate use | 30-50% | Durability, ease of printing, functional fit. |

| Enclosure for Electronics | Protection, housing | 15-25% | Lightweight, ease of assembly, dust/debris protection. |

Strategies for Adjusting Infill Density for Prototypes Versus End-Use Parts

The distinction between prototypes and end-use parts is crucial when deciding on infill density. Prototypes serve different purposes at various stages of development, while end-use parts must meet specific performance criteria for their intended lifespan. Adapting infill density accordingly optimizes resources and ensures functional success.For prototypes, the primary goals are often rapid iteration, cost-effectiveness, and validating design concepts. Therefore, infill density can be adjusted to facilitate these objectives:

- Early-Stage Visual Prototypes: These are primarily for form and fit checks. Very low infill densities (5-15%) are typically sufficient. This minimizes print time and material waste, allowing for quick design validation.

- Mid-Stage Functional Prototypes: When testing basic mechanical function or ergonomics, a slightly higher infill density (15-30%) might be employed. This provides enough strength to simulate basic usage without over-engineering.

- Late-Stage Functional Prototypes: If the prototype is intended to closely mimic the performance of the final part, a higher infill density might be used, approaching that of the end-use part, but still with room for potential design tweaks.

For end-use parts, the focus shifts entirely to performance, durability, and reliability. The infill density must be sufficient to withstand the operational stresses and environmental conditions for the expected service life of the part.

- Performance-Driven Infill: End-use parts require an infill density that guarantees the necessary strength, stiffness, and impact resistance. This often means selecting a density from the higher ranges (50-100%) depending on the application’s demands.

- Material Optimization for Longevity: While high infill provides strength, it also increases material usage and print time. For end-use parts, a balance is struck to achieve the required performance with optimal material consumption, considering the cost of materials and potential for part failure.

- Testing and Validation: End-use parts should undergo rigorous testing to confirm that the chosen infill density, along with material selection and print settings, meets all performance specifications. This might involve load testing, fatigue testing, or environmental exposure tests.

- Consideration of Infill Patterns: For end-use parts, the choice of infill pattern becomes even more critical. Patterns like gyroid or cubic can offer better strength distribution and isotropic properties compared to simpler patterns like grid, especially at lower infill percentages.

Exploring Different Infill Patterns and Their Significance

While infill density dictates the amount of material within a print, the infill pattern determines how that material is arranged. This arrangement profoundly influences the strength, weight, print time, and even the aesthetic of your 3D models. Understanding these patterns allows for a more nuanced approach to optimizing your prints, complementing the effects of density and catering to specific application needs.The internal structure of a 3D print is not simply a solid block of plastic.

Instead, it’s a carefully designed lattice that provides support and defines the object’s mechanical properties. Different patterns offer unique trade-offs, and selecting the right one is as crucial as choosing the correct density.

Common Infill Patterns and Their Visual Characteristics

Infill patterns are the geometric arrangements of the extruded filament within the hollow parts of a 3D model. They are the internal scaffolding that gives the object its form and strength. Each pattern has a distinct visual signature when viewed in a cross-section, offering unique benefits.

- Grid: This pattern features a crisscross arrangement of lines, forming a grid of squares or rectangles. It is a straightforward and widely used pattern, known for its simplicity and good strength in multiple directions.

- Honeycomb: As the name suggests, this pattern creates a tessellation of hexagonal cells. Hexagons are known for their structural efficiency, distributing stress evenly and offering excellent strength-to-weight ratios.

- Gyroid: This pattern is characterized by smooth, continuous, and intertwined curves that form a three-dimensional labyrinth. It offers excellent multi-directional strength and is known for its aesthetic appeal and vibration-dampening properties.

Structural Advantages and Disadvantages of Infill Patterns

The choice of infill pattern significantly impacts a model’s mechanical performance. Some patterns excel in specific types of stress, while others might be more prone to failure under certain loads. Understanding these characteristics is vital for selecting the most appropriate pattern for your application.

| Infill Pattern | Structural Advantages | Structural Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Grid | Good omnidirectional strength, simple to implement, fast printing times compared to some complex patterns. | Can be prone to delamination along the lines if subjected to shear forces, less efficient use of material for certain stress types. |

| Honeycomb | Excellent strength-to-weight ratio, good shear strength, efficient material usage, resists crushing forces well. | Can be slower to print than grid due to more complex geometry, may require more support material in some slicing configurations. |

| Gyroid | Exceptional multi-directional strength, good vibration damping, aesthetically pleasing internal structure, efficient for complex shapes. | Can be slower to print than grid or honeycomb due to its complex curves, may require careful calibration for optimal deposition. |

Infill Pattern’s Complementary Role with Infill Density

The effectiveness of an infill pattern is intrinsically linked to the infill density. A low infill density with a strong pattern might still yield a weak part, while a high density with a less efficient pattern might be unnecessarily heavy and slow to print. The interplay between these two settings allows for fine-tuning.For instance, a high infill density with a Grid pattern will create a very robust structure, but it might be overkill for applications not requiring extreme strength.

Conversely, a low infill density with a Honeycomb pattern can provide surprisingly good strength for its weight, making it ideal for functional prototypes where weight is a concern. The Gyroid pattern, even at lower densities, can offer superior impact resistance due to its continuous nature, effectively absorbing energy.

Visualizing Internal Structures with Various Infill Patterns

To truly appreciate the differences, imagine slicing a model in half. With a Grid pattern, you would see a series of parallel lines running in two perpendicular directions, forming a repeating square or rectangular mesh. This creates distinct layers of support.When visualizing a Honeycomb pattern, the cross-section reveals a network of interconnected hexagons, like a microscopic beehive. Each cell is a closed structure, contributing to a uniform distribution of stress across the entire infill volume.A Gyroid pattern, when viewed in cross-section, appears as a smooth, flowing, and interconnected series of curves.

It’s less about distinct lines or cells and more about a continuous, organic-looking lattice that seamlessly blends into itself, offering a more uniform and less rigid feel than the other two. This visual complexity hints at its superior multi-directional support and energy absorption capabilities.

Practical Considerations for Setting Infill Density

Understanding the theoretical impact of infill density is crucial, but translating that knowledge into successful prints requires a practical approach. This section delves into the real-world application of setting infill density, focusing on how to interact with your slicing software, validate your choices, and avoid common missteps. We will also explore an advanced technique that can significantly optimize your prints.

Accessing and Modifying Slicer Software Settings

Slicer software is the bridge between your 3D model and your 3D printer, and it’s where you’ll directly control infill density. While the exact layout can vary between slicers like Cura, PrusaSlicer, or Simplify3D, the fundamental process remains consistent. Locating and adjusting these settings is a straightforward task once you know where to look.

In most slicer applications, infill settings are typically found within the “Quality,” “Shell,” or “Infill” sections of the print settings. You will usually see a numerical input field labeled “Infill Density” or “Infill Percentage.” This value is expressed as a percentage, where 0% represents no infill (hollow) and 100% represents a solid model. By default, slicers often suggest a moderate infill density, such as 10-20%, for general-purpose prints.

To modify the infill density, simply click on the numerical input field and type in your desired percentage. For example, if you need a stronger part, you might increase the infill density from 15% to 40%. Conversely, if you are prioritizing speed and material savings for a non-critical part, you could reduce it to 5%.

Best Practices for Performing Test Prints

Validating your infill density choices through test prints is an essential step to ensure you achieve the desired balance of strength, weight, and print time. This iterative process allows you to fine-tune settings before committing to a large or complex print.

The most effective way to test infill density is to print small, representative sections of your model or simplified test objects that mimic the structural demands of your final print. Consider printing cubes, cylinders, or specific critical components of your larger design. These test prints should be identical in all settings except for the infill density you are evaluating.

- Start with a Baseline: Print a test object with your slicer’s default infill density or a commonly used value (e.g., 15-20%) to establish a reference point.

- Incremental Adjustments: Make gradual changes to the infill density for subsequent test prints. For instance, if your baseline is 15%, try 10%, then 20%, and then 30% to observe the differences.

- Stress Testing: After printing, physically test the strength of your test objects. This could involve bending, pressing, or even dropping them (depending on the intended application) to assess their durability.

- Weighing and Measuring: Compare the weight of your test prints. A higher infill density will result in a heavier part, which can be an important consideration for some applications.

- Print Time and Material: Keep track of the print time and material used for each test. This helps you understand the trade-offs between strength and efficiency.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid When Setting Infill Density

While setting infill density seems straightforward, several common mistakes can lead to suboptimal results. Being aware of these pitfalls can save you time, material, and frustration.

- Over-Infilling for Non-Critical Parts: Applying a high infill density (e.g., 80-100%) to parts that do not require significant structural integrity is a common waste of material and print time. This can also lead to internal stresses and potential warping.

- Under-Infilling for Critical Components: Conversely, using too low an infill density for parts that will undergo stress can result in premature failure, regardless of the outer shell strength.

- Ignoring Material Properties: Different filament types (PLA, ABS, PETG) have varying strengths and flexibilities. An infill density that is perfect for PLA might be insufficient for ABS under the same load.

- Not Considering Layer Adhesion: Very high infill densities, especially with certain infill patterns, can sometimes lead to poor layer adhesion within the infill structure itself, creating internal weak points.

- Failing to Calibrate the Printer: Inaccurate extrusion rates or bed leveling can exacerbate issues related to infill density, making test prints unreliable. Always ensure your printer is properly calibrated before fine-tuning infill.

Variable Infill Density Within a Single Model

A powerful technique that offers significant advantages is the use of variable infill density. This advanced feature allows you to specify different infill percentages for different parts of the same model, optimizing for both strength and efficiency.

Variable infill density is particularly useful for complex models where certain areas are subjected to higher mechanical stress than others. For example, a bracket might require a high infill density in the mounting holes and load-bearing sections, while less critical areas can have a much lower infill density to save material and print time.

Most modern slicer software supports variable infill density through various methods:

- Per-Object Settings: In some slicers, you can assign different print settings, including infill density, to individual objects placed on the build plate. This is useful if you are printing multiple components with varying requirements.

- Modifiers/Perimeters: Advanced slicers allow you to use modifier meshes or custom supports to define specific regions within a single model where infill density can be altered. You essentially “paint” or define areas with different infill settings.

- Layer-Based Infill: Some slicers offer the ability to change infill density based on the layer height. This means you could have a denser infill at the base of a part for stability and a lighter infill towards the top.

The benefits of variable infill density are substantial:

Variable infill density allows for optimized part performance by concentrating material only where it is needed, leading to reduced print times, lower material consumption, and lighter-weight yet functionally robust 3D printed objects.

Implementing variable infill density requires careful planning and understanding of your model’s stress points. By strategically applying higher infill densities to critical areas and lower densities to less stressed regions, you can achieve prints that are both strong and economical.

Advanced Techniques and Optimization

Moving beyond the fundamental understanding of infill density, this section delves into sophisticated methods for fine-tuning infill settings to achieve highly specific performance characteristics and resolve complex printing challenges. We will explore how to leverage infill density for structural integrity, aesthetic control, and efficient material usage, ultimately leading to more robust and precisely engineered 3D printed objects.

Calculating Optimal Infill Density Based on Load-Bearing Requirements

Determining the precise infill density needed to withstand specific mechanical stresses is a crucial aspect of advanced 3D printing for functional parts. This involves a systematic approach that combines engineering principles with practical printing considerations.The process typically begins with identifying the critical load points and expected forces acting upon the model. This information can be derived from engineering simulations, stress analysis software, or empirical testing of similar components.

Once the maximum expected load is understood, a safety factor is applied to account for variations in material properties, printing inaccuracies, and unexpected environmental conditions.A simplified approach to calculating required infill density for tensile or compressive strength can be conceptualized using the following relationship, though it’s important to note that real-world applications often require more complex finite element analysis (FEA):

Required Infill Strength = Maximum Expected Load x Safety Factor

The infill’s contribution to the overall strength of a part is directly proportional to its density and the strength of the chosen infill pattern. Different infill patterns offer varying degrees of strength in different directions. For instance, a gyroid infill might offer more isotropic strength compared to a rectilinear infill, which is stronger along its printed lines.To translate the required infill strength into a percentage of infill density, one would typically consult material datasheets and perform experimental testing.

For example, if a specific infill pattern at 100% density can withstand a certain load, then the required infill density percentage can be estimated by:

Estimated Infill Density (%) = (Required Infill Strength / Maximum Strength at 100% Infill) x 100

However, this is a highly generalized formula. A more accurate method involves using FEA software that can model the infill structure and its mechanical response under load. These tools allow for the direct simulation of stress distribution within the infill, enabling the optimization of density and pattern to meet specific performance targets without over-engineering and wasting material. For example, a bracket designed to hold a specific weight might require a higher infill density in the areas directly supporting the load, while less critical areas can utilize a lower density.

Achieving Specific Surface Finishes and Internal Support Structures

Infill density and pattern settings play a significant role not only in structural integrity but also in influencing the external surface finish and providing internal support where needed. Understanding these relationships allows for greater control over the final appearance and functionality of a print.The external surface finish can be indirectly affected by infill density through several mechanisms:

- Surface Waviness: In models with thin walls or complex geometries, the infill pattern can sometimes show through to the outer surface, creating a subtle ripple or waviness. Higher infill densities, especially with patterns that are less prone to telegraphing (like gyroid or cubic), can help to mitigate this effect by providing a more solid base for the outer walls.

- Warping and Shrinkage: A denser infill can provide better support for outer walls during the cooling process, reducing the likelihood of warping or shrinkage that can mar the surface finish.

- Post-Processing: For models intended for painting or other surface treatments, the infill density can impact how well the surface accepts these treatments. A denser infill might provide a more uniform substrate for paint adhesion.

Infill settings can also be strategically used to create internal support structures, reducing the need for external support material. This is particularly useful for models with internal cavities or overhangs that would otherwise be difficult to print.

- Support Structures within Cavities: By increasing the infill density in specific internal regions or by selecting infill patterns that naturally create bridges or supports, designers can enable the printing of complex internal geometries without the need for dissolvable supports, which can be difficult to remove from tight spaces. For example, printing a hollow sphere with internal latticework created by a high-density infill pattern can allow for the successful printing of the sphere’s internal structure.

- Bridging Assistance: Certain infill patterns, when printed at appropriate densities, can act as internal scaffolding to assist in bridging over gaps, thus reducing the amount of external support needed.

Experimentation with different infill densities and patterns is often required to achieve the desired balance between surface quality and internal support. For instance, a model with a very smooth exterior requirement might necessitate a lower infill density with a robust outer wall, while a model requiring intricate internal features might benefit from a higher, more supportive infill.

Troubleshooting Infill Density-Related Print Failures and Weak Points

Infill density is a common culprit when it comes to print failures and the development of weak points in 3D printed models. A systematic approach to troubleshooting can help identify and resolve these issues effectively.Common problems associated with incorrect infill density include:

- Print Failures (e.g., Layer Shifting, Bed Adhesion Issues): While not directly caused by infill density, an excessively dense infill can lead to longer print times and increased material extrusion, potentially causing the print head to snag or exert undue pressure on the print bed, leading to shifts or detachment. Conversely, an infill that is too sparse may not provide adequate adhesion to the base layers or subsequent walls, leading to delamination.

- Weak Points and Structural Integrity Issues: The most direct consequence of improper infill density is a part that fails under load. If the infill density is too low, the internal structure will not be strong enough to support the intended forces, leading to breakage or deformation. Conversely, an infill that is too dense, especially with certain patterns, can sometimes introduce internal stresses or print defects that create weak points.

- Stringing and Oozing: While primarily related to retraction settings and filament temperature, an extremely high infill density can increase the amount of filament that needs to be moved and extruded, potentially exacerbating stringing issues if retraction is not perfectly tuned.

- Over-extrusion and Under-extrusion within the Infill: If the infill density is set too high for the printer’s capabilities or the chosen speed, it can lead to over-extrusion, where too much material is deposited, potentially causing jams or rough internal surfaces. Too low a density, or printing too fast for the infill, can result in under-extrusion, leading to gaps and weak connections.

A troubleshooting workflow can be structured as follows:

- Analyze the Failure: Carefully examine the failed print. Is the failure at the base, mid-section, or top? Are there visible gaps, cracks, or signs of material deformation? Document the infill density and pattern used for the print.

- Review Load Requirements: Re-evaluate the expected loads the part needs to withstand. Is the current infill density sufficient? Consult engineering principles or simulation data if available.

- Inspect Slicer Settings:

- Infill Density: If the part is weak, gradually increase the infill density in increments of 5-10%. If print failures are occurring, consider if the density is excessively high, leading to prolonged print times or material buildup.

- Infill Pattern: Certain patterns are inherently stronger or more suitable for specific load types. For example, gyroid or cubic patterns offer better multi-directional strength than rectilinear.

- Wall Thickness: Ensure that the outer walls are sufficiently thick to contain the infill and provide primary structural support.

- Print Speed for Infill: Slower infill speeds can improve adhesion and layer consistency, especially for complex or dense infill patterns.

- Material and Printer Calibration: Ensure the filament is dry and that the printer is properly calibrated for extrusion, temperature, and bed leveling. These factors can significantly impact the quality and strength of the infill.

- Test Prints: Print small, representative sections of the model with varying infill densities and patterns to identify the optimal settings before committing to a full print.

- Iterative Refinement: Based on test print results, adjust infill density, pattern, and other related settings in small increments and repeat the testing process until the desired strength and print quality are achieved.

Workflow for Iterative Refinement of Infill Density Settings for Complex Designs

For intricate designs that demand precise performance and aesthetic qualities, an iterative refinement workflow for infill density settings is essential. This systematic approach ensures that optimal parameters are discovered through a process of controlled experimentation and analysis.The workflow can be Artikeld as follows:

- Define Performance Objectives: Clearly articulate the primary goals for the infill. This could include specific load-bearing capacity, weight reduction targets, desired surface finish, or the need for internal structural support.

- Initial Parameter Selection: Based on the design’s complexity, expected stresses, and material properties, select an initial infill density and pattern. This selection should be informed by previous experience, material datasheets, or basic engineering calculations. For a complex mechanical part, start with a moderate density (e.g., 20-40%) and a strong pattern like gyroid or cubic.

- Prototyping and Testing: Print a scaled-down version or a critical section of the design with the initial infill settings. Subject this prototype to relevant stress tests, visual inspections, and functional evaluations according to the defined objectives.

- Analyze Test Results: Document all findings from the testing phase. Note any signs of weakness, deformation, surface imperfections, or printing difficulties. Quantify performance where possible (e.g., load at failure).

- Adjust Parameters and Re-test: Based on the analysis, make informed adjustments to the infill density and pattern.

- If the prototype shows weakness, increase infill density or switch to a pattern with better strength characteristics.

- If the part is over-engineered or too heavy, consider reducing infill density or exploring lighter, yet structurally sound, patterns.

- If surface finish is compromised, experiment with infill patterns that are less likely to telegraph through walls or adjust wall thickness.

Print a new prototype with the adjusted settings and repeat the testing process.

- Iterate until Optimization: Continue this cycle of testing, analysis, and adjustment until the infill density settings meet all the defined performance objectives within acceptable tolerances. This may involve multiple iterations.

- Consider Material and Printer Variables: Throughout the process, remain mindful of how material properties (e.g., brittleness, flexibility) and printer capabilities (e.g., extrusion accuracy, cooling effectiveness) might influence the infill’s performance. Adjustments to other print settings, such as print speed, layer height, or temperature, may be necessary in conjunction with infill modifications.

- Final Verification: Once satisfactory infill settings are identified, print the full model and perform final verification tests to ensure it performs as expected in real-world conditions.

This iterative workflow is particularly valuable for complex geometries where intuition alone may not suffice. For example, a drone chassis designed for both lightweight construction and impact resistance would benefit immensely from this methodical approach, ensuring that the infill density is optimized for strength in critical areas while minimizing weight in less stressed regions.

Ending Remarks

By carefully considering the interplay of infill density, pattern, and application-specific needs, you can unlock the full potential of your 3D printer. This journey through optimizing infill density empowers you to create models that are not only visually appealing but also robust, efficient, and perfectly suited to their intended purpose, transforming your design concepts into tangible realities with confidence.